|

|

ECE 2100 |

Lab

Work (continued)

- Part D: Serial and parallel concept

What are the

functions or applications of

electrical circuits?

For virtually

all of them, there are three major

applications:

- power distribution,

- signal/information processing (communication/computing), and

- control (related to signal processing).

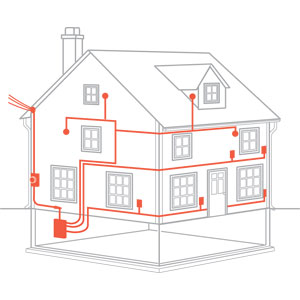

Consider the simplest power distribution application that we all are familiar with:

The household circuit is designed

to distribute the power from the

street or electrical pole to

appliances in the house. The

appliances should be independent

from each other, hence, each is

directly wired to the power

source, resulting in parallel

configuration. An essence of

the parallel configuration power

distribution is that it must be a

voltage source, which supplies

variable current to the demands,

up to the maximum current capacity.

A circuit short can take up the

entire current capacity, and all

other appliances will fail.

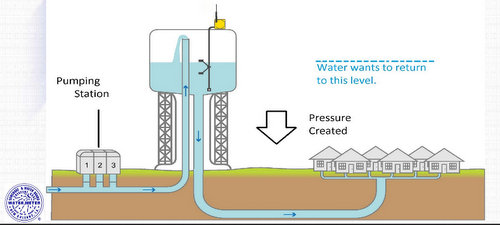

An analogy of

parallel circuit is the water

distribution system to the home:

Every

household has the same

pressure, but the water

flow rate can vary

depending on usage.

The

opposite of parallel configuration

is the serial configuration.

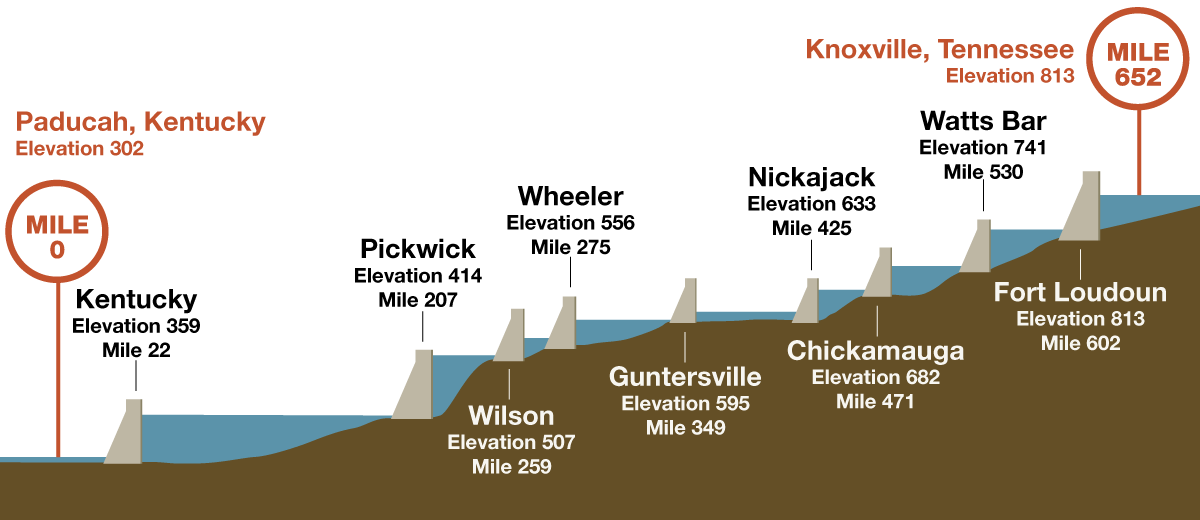

Consider another analogy:

Assume for

simplicity that a river

volume is conserved over its

course (neglecting minor water

adding and subtraction from small

tributary streams and rivulets),

then the water pressure or

potential energy can vary over

different segments as illustrated

above, but the flow rate is the

same (water mass conservation). If

each dam produces hydroelectricity

with identical turbine system for

all dams using the same water flow

rate, the power output would be

different depending on the

pressure differential (water

potential energy) at each dam.

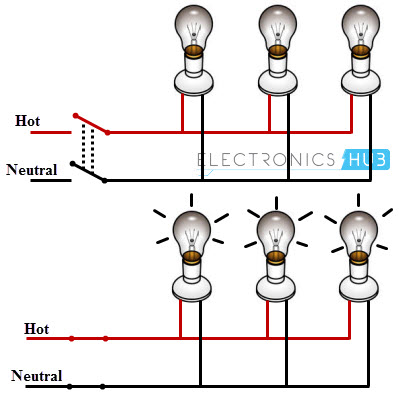

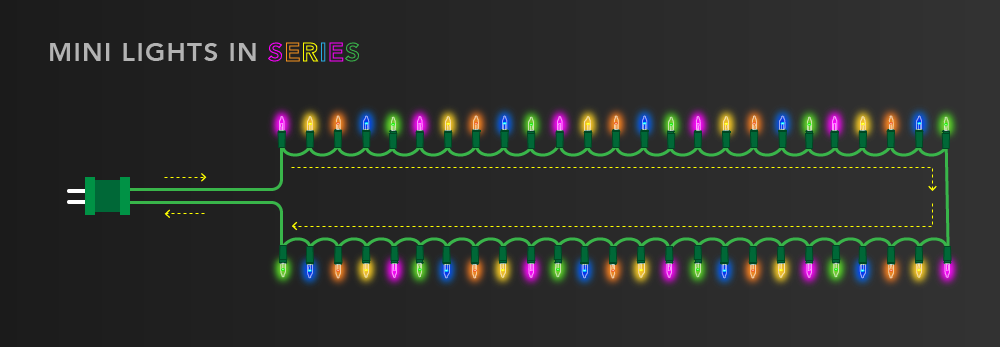

In the old

time, we sometimes see serial

circuits such as the one below:

The

advantage of this

configuration is that a

small current (low risk of

fire) can be used with

high voltage to supply the

power. The disadvantage is

well known: if

a light is broken (open) or

removed, it breaks the current and

the entire circuit is off. But if

a light is shorted, the circuit is

still working.

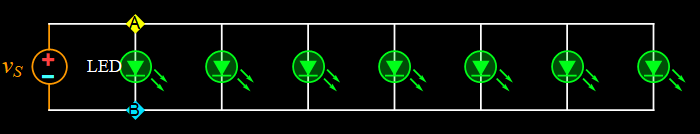

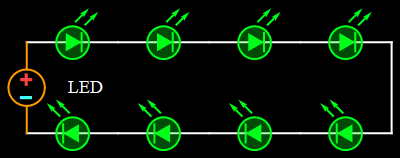

For Part D, we

will study two very simple

examples below:

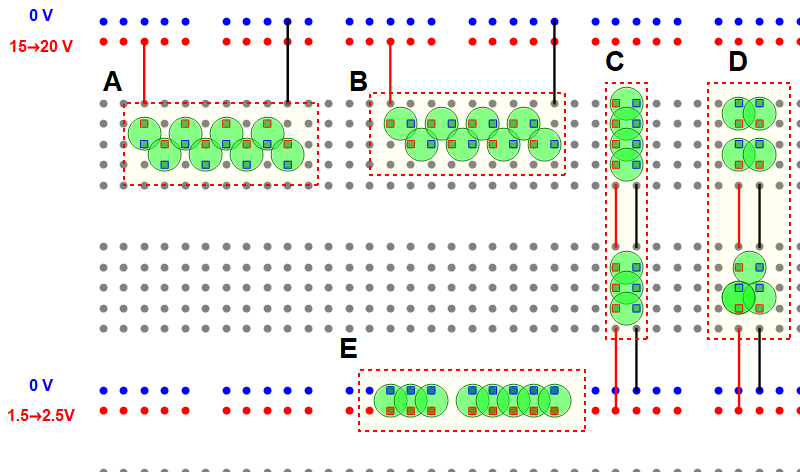

Fig. 4.1 |

All LED's should be

of the same color. If you are short

of LEDs of the same color, you can

mix LEDs of very close colors, such

as mixed red/orange, or mixed

yellow/green. Blue cannot be mixed

with any other color (unless you

have purple). The circuit is

scalable, the number of LED's can

range from 4 - 8 depending on how

many you have. |

Fig. 4.2 |

Same as above with

regard to LED color. |

To implement

circuits in Fig. 4.1 and 4.2 onto

a breadboard, consider Fig. 4.3

below.

Fig. 4.3

Figure 4.3

above shows 5 wiring

configurations of group of LED's,

labeled A, B, C, D, E. The last

block, configuration E, is the

obvious diagram of 8 LEDs in

parallel. It is shown only for

illustration. For the Lab work of

Part D:

- determine

which of A, B, C, D LED blocks

represents the circuit in Fig. 4.2

- build the circuit, apply the

voltage while monitoring the

current until the current is 15±1

mA. (if your LEDs are too dim,

raise the current to the level you

feel sufficient to see).

- measure the voltage and obtain

the total power (P= V x I).

Divide the total power by the

number of LEDs to determine the

average power per LED.

- determine which

of A, B, C, D LED blocks

represents the circuit in

Fig. 4.1

- build the

circuit, apply the

voltage while

monitoring the

current until the

current is n*15±1

mA where n is the

number of

LEDs. For

example, if n=7,

the current should

be 7*15 mA=105±5 mA.

-

measure the

voltage and obtain

the total power

(P= V x I).

Divide the total

power by the

number of LEDs to

determine the

average power per

LED.

- compare

the per-LED power

of circuit 4.2 and

circuit 4.1.

Discuss.

- discuss

what's wrong with

the other circuits

that are not

selected for

measurement.

- Part E: Parallel current distribution

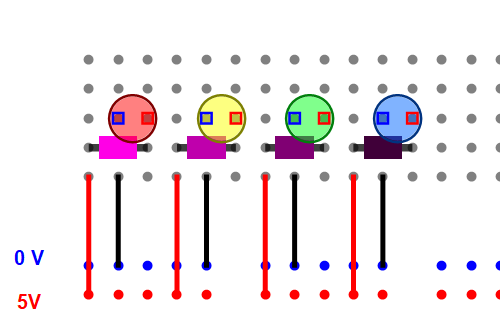

Fig.5.1 |

Consider the circuit

in Fig. 5.1. The 4 LEDs should be

red, yellow, green, blue. The

resistors are of your choice such

that the current in each LED should

be approximately 15 ± 5 mA.

(depending on your LED type, you can

go higher or lower, as long as it is

safely below the damage threshold of

the LEDs - check with manufacturer's

specs). Use the app in Section 3

(Part C) to get an estimate for the

resistance value for each LED. Use

resistors in parallel if necessary

to obtain the value you need. Work to be done and reported: - draw the entire circuit schematic with measured resistance values (after selecting appropriate resistors) - measure the current of each LED circuit, which should be 15 ± 5 mA as indicated above - measure the voltage of each LED - measure the net current supplied by the voltage source (nothing else should be connected to the voltage source besides this circuit). Verify if the measured net current is equal to the sum of all LED currents. |

Hint: see the

figure below. The calculation uses

a fixed value of R1 for all LED

colors. Hence, it is up to you to

find and match the resistance for

each LED color such that the

current is as close to 15 mA as

possible.

END